Ferdinand Gonseth

Ferdinand Gonseth was born in 1890 as the son of a watchmaker in Sonvilier in the Bernese Jura. He studied physics and mathematics at the ETH Zurich despite a very severe visual impairment. In 1920 he became professor of general mathematics at the University of Bern. Nine years later he returned to the ETH as professor of higher mathematics in French. There he was also appointed full professor of philosophy of natural sciences in 1946. In the same year he co-founded the Internationale Gesellschaft zur Pflege der Logik und Philosophie der Wissenschaften (International Society for the Cultivation of Logic and Philosophy of Science). A year later, in 1947, he founded the journal Dialectica together with Bernays and Bachelard.

Paul Bernays

Paul Bernays was born in London in 1888 as the son of a merchant. He grew up in Berlin and studied mathematics, philosophy and theoretical physics in Berlin and Göttingen. In 1912 he habilitated at the University of Zurich and became a private lecturer there. After teaching in Göttingen for several years, he was dismissed in 1934 because of his Israeli origin and returned to Switzerland, where he worked as an associate professor of higher mathematics at the ETH Zurich from 1945 on. Together with Gonseth, he co-founded the Internationale Gesellschaft zur Pflege der Logik und Philosophie der Wissenschaften (International Society for the Cultivation of Logic and Philosophy of Science) in 1946 and Dialectica a year later.

Gaston Bachelard

Gaston Bachelard was born in 1884 as the son of a tobacco merchant in the French Champagne region. Despite financially difficult conditions and an interruption due to 38 months of service in the First World War, he studied mathematics, physics, chemistry and philosophy. After several years as a high school teacher and later philosophy professor at the University of Dijon, he was appointed to the Sorbonne in 1940, where he held the chair of History and Philosophy of Science. There he also became director of the Institut d'Histoire des Sciences et des Techniques (Institute for the History of Science). In 1947, he founded Dialectica together with Gonseth and Bernays.

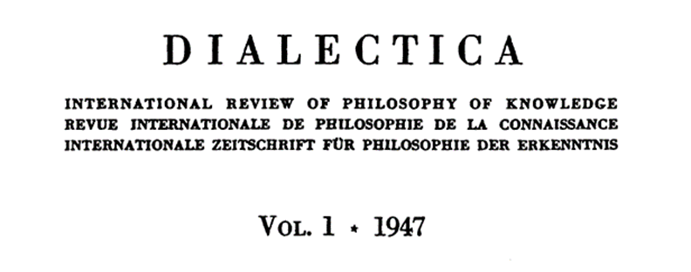

The first edition

Already in the founding year, four different issues of Dialectica appeared. The first issue was published on 15 February 1947. Under the name on the title page, Dialectica is called “Internationale Zeitschrift für Philosophie der Erkenntnis” (international journal for the philosophy of knowledge).

The multilingualism already begun on the first page runs through the edition: While the headings and the preface have been translated into all three languages, the essays and acknowledgements are written in German and/or French.

In keeping with the naming of the journal, the theme of this first issue was "Die dialektische Denkweise" (the dialectical way of thinking). In addition to the preface, the number contains six philosophical essays, among others by Bachelard and Gonseth himself. In addition, there is a philosophical portrait of Leibniz on the occasion of the 300th anniversary of his birth and an essay on the current state of philosophy .

The journal was published by Presses Universitaires de France Paris and Éditions du Griffon Neuchâtel Suisse, with rights held by the latter.

Aims and philosophical orientation

In the preface to the first edition, the authors (it is not stated by whom it was written) provide insights into the background and purpose of Dialectica. In doing so, they focus on the intention to engage in an era with whose way of thinking one cannot identify: They do not want to retreat, but to work for the time in which they live. These reflections are embedded in a larger scholarly context: They refer to their time as the "Zeitalter der Wissenschaft" (age of science), which is characterised by the fact that the knowledge of the specialist has "die Grenzen des gemeinhin Ersichtlichen überschritten" (transcended the limits of what is commonly apparent). However, the forces released by this knowledge also harbour dangers. This is the context in which the authors set their philosophical objective:

«Was sollen wir tun um mit diesem Wissen Schritt zu halten, was tun um es einzugliedern in eine Kultur der menschlichen Werte ? Damit uns dieses Wissen nicht entgleite, damit es andererseits durch die Erfordernisse seiner Handhabung und Anwendung nicht zum Herren über uns werde, ist eine Leistung unsererseits nötig, eine entschiedene und beständige philosophische Leistung.»

Translation: "What should we do to keep up with this knowledge, what should we do to integrate it into a culture of human values? So that this knowledge does not slip away from us, so that on the other hand it does not become master over us through the requirements of its handling and application, a performance on our part is necessary, a decisive and constant philosophical performance."

What does this mean for philosophy? The authors feel obliged to preserve the coherence of total knowledge, to stand up for the preservation of uniform guidelines concerning the methods of finding objective knowledge and to supervise that our intentions in these undertakings remain unadulterated. For philosophy, this means not hiding behind dogmatism and the notion of absolute validity. They want to go beyond the boundaries of their own discipline, to remain open to new things, especially new experiences. In this sense, the empirical sciences represent for them the breeding ground for philosophy.

Sources (German)

Thomas Fuchs: "Bernays, Paul", in: Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (HLS), Version vom 04.04.2022. Hier. Konsultiert am 23.10.2022.

Thomas Fuchs: "Gonseth, Ferdinand", in: Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (HLS), Version vom 04.01.2007. Hier. Konsultiert am 23.10.2022.

Webseite der Association Internationale Gaston Bachelard. Hier. Konsultiert am 25.10.22

Wikipedia-Artikel zu Dialectica. Hier. Konsultiert am 25.10.2022

Wikipedia-Artikel zu Gaston Bachelard. Hier. Konsultiert am 25.10.22

Erste Ausgabe von Dialectica. Hier.

Images

Paul Bernays: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Bernays

Gaston Bachelard: Von Autor/-in unbekannt - [1] Dutch National Archives, The Hague, Fotocollectie Algemeen Nederlands Persbureau (ANEFO), 1945-1989 bekijk toegang 2.24.01.04 Bestanddeelnummer 917-9599, CC BY-SA 3.0 nl, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=37090666

Ferdinand Gonseth: Fr. Schmelhaus / ETH Zürich - ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Bildarchiv (Wikipediaseite über Ferdinand Gonseth)

Erste Ausgabe von Dialectica. Hier.