What makes you, you? What could be changed or removed and still leave the ‘youness’ intact? More specifically, what is required for you to persist: to be the same person tomorrow as you were yesterday?

Fiction and philosophy alike have offered various ways to answer this question. They tend to approach the problem in similar fashion as well: they ask us to entertain some pretty strange hypotheticals – be they thought experiments or fictional scenarios (what’s the difference, really?) – and then see what intuitions fall out.

One of the classic personal identity thought experiments is called Theseus’s Ship. It goes like this:

Over a period of years, in the course of maintenance a ship has its planks replaced one by one – call this ship A. However, the old planks are retained and themselves reconstituted into a ship – call this ship B. At the end of the process there are two ships. Which is the original ship of Theseus?[1]

People differ in their response: some think ship A – after all, it’d be the one they’d insured – and others think ship B (including those looking for forensic evidence of the bloody murder you committed before deciding to overhaul your ship). Some think there isn’t a clear answer one way or the other, or that they’re both the original ship (whatever that means).

We find variants of Theseus’s Ship throughout our fiction. In the Doctor Who episode Deep Breath, the Twelfth Doctor asks,

If you have a broom, you replace the handle, and then you replace the brush, and do it over and over, is it still the same broom?

(We might, of course, ask the same question of the Doctor).

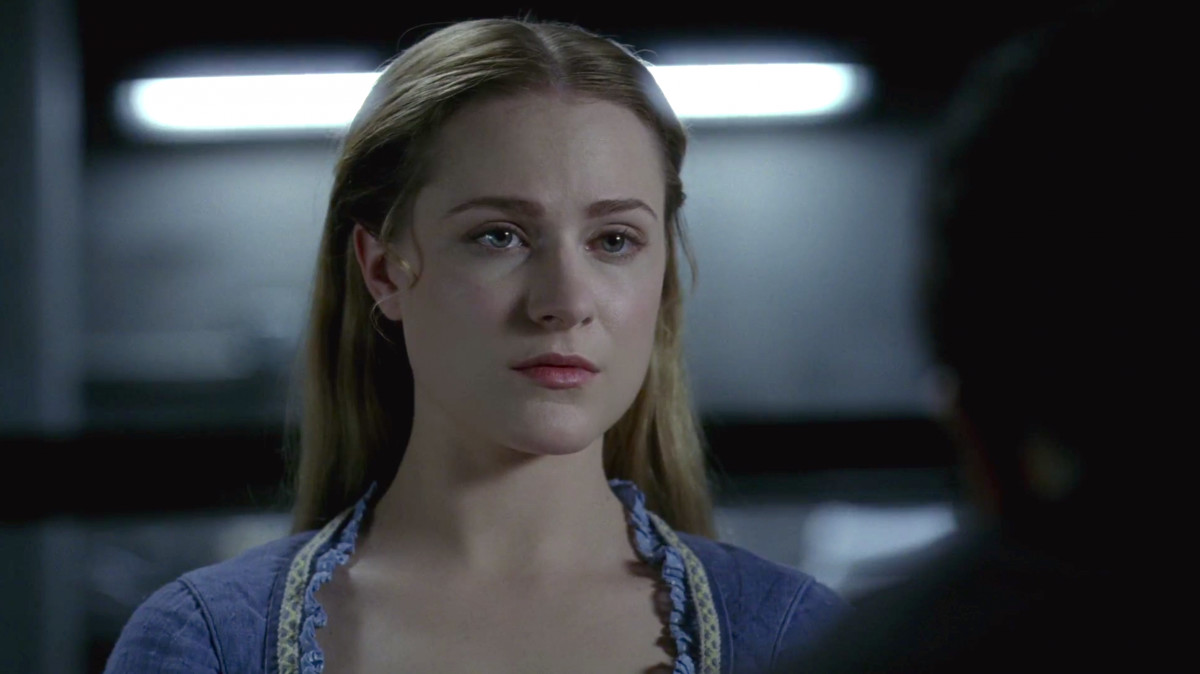

And in Westworld (which is full of interesting musings about identity, but here’s just a small example) we hear of Dolores:

You know why she's special?

She's been repaired so many times, she's practically brand-new.

Don't let that fool you. She's the oldest host in the park.

Westworld, S01E01

I am inclined to think that Dolores continues to be Dolores, despite her modifications and repairs. Likewise, I can accept that each incarnation of the Doctor is, in some sense, the same continuing Time Lord (your intuitions might differ from mine – in which case, tell me in the comments!). Perhaps the Ship of Theseus example is extra tricky because there are two ships: if the old planks had been left to rot, rather than reassembled, maybe our intuitions would be clearer.

Many people would write off these questions as idle speculation: a matter best left for sci-fi, or philosophers in their ivory towers. But I am confident that you, dear reader, know better. After all, your cells die and are replaced. Your thoughts change – you’ve gained and lost memories over time, changed your convictions, developed your dispositions. The planks that make up you are no more permanent than those in Theseus’s Ship. So what is it that enables you to persist, despite the changes you’ve undergone, from one day to the next?

“If you have a broom, you replace the handle, and then you replace the brush, and do it over and over, is it still the same broom?”

Material Continuity

We might answer the persistence question in terms of material continuity:

You are that past or future being that has your body, or that is the same biological organism as you are, or the like.[2]

That body can undergo change, but so long as there is some physical continuity between the different stages of you – baby, toddler, misunderstood teen etc. – there is persistence. In fiction we’re willing to believe that a person can undergo a great deal of change and persist. Upon seeing Hermione’s failed Polyjuice Potion transformation in Chamber of Secrets, did you stop, in outrage, and exclaim ‘Oh my god they’ve killed Hermione! A giant cat-person has taken her place!’

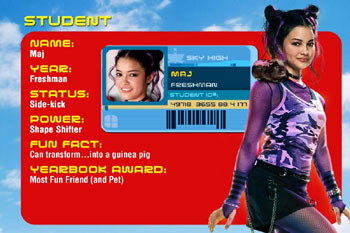

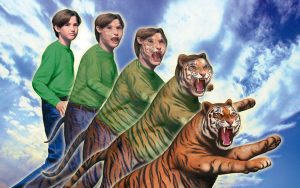

Of course you didn’t. Just like you don’t worry that Bruce Banner has died when the Hulk appears, or that Jacob has ceased to be when he leaps into wolf-form. And remember that kid from Sky High who could turn into a guinea pig?

The whole premise of Animorphs is that people can drastically change their bodies and yet remain fundamentally the same person. The body can change a great deal – indeed, undergo full metamorphosis[3] – and yet we’re still willing to believe the person remains intact.

That’s not always the case though – sometimes we can go too far. You might believe that your BFF has turned into a beetle, a werewolf, or a luminescent green beefcake, but you mightn’t be so optimistic about their continued existence if they had been transformed into a tea cosy.[4]

In fictional worlds without magic – including, perhaps, the world we live in – the brain is often the limit. We can survive losing a few limbs, organs, even everything below the neck, but it’s the brain that makes us who we are. Thus we can make sense of brain swap stories, where characters wake up in new bodies.

But is the brain really the limit?

Psychological Continuity

In more recent fiction, the brain swap has been superseded by the brain scan, where it isn’t the brain meat that matters (the hardware) but rather the mental content (the software), frequently thought to include memories, beliefs, desires and so forth – all the stuff thought to make up our personality. There are both sci-fi and fantasy variants of this idea: the brain upload/download in the former case – think the baddies in The Sixth Day, the avatars in, well, Avatar, or the Cylons in Battlestar Galactica – and the Freaky Friday flip in the latter.

What exactly is required for persistence – even of the psychological variety – differs between accounts, both fictional and philosophical. One common but contentious possibility is memory. A particularly pervasive trope is the Quest for Identity, which occurs when a character

wakes up stranded in the middle of nowhere, with no recollection of who he is. The plot involves, at least in part, his efforts to discover the identity he cannot remember.[5]

We are used to characters exclaiming, ‘I can’t remember who I am!’

See? But there is a difference between knowing who you are and being the same person over time: the former is an epistemic matter and the latter a metaphysical one. When thinking about persistence, it is the latter that we should have in mind.

Here are two strikingly different takes on the importance of memory for identity:

In the film version of Allegiant (which proved, if nothing else, that sometimes it’s better to write just one book rather than making everything a trilogy), Four discovers that some children are going to have their memories wiped. He is horrified by this, and pleads,

If you take away what they know, you take away who they are.

When the Dollhouse’s madam Adelle Dewitt discovers Echo poking about some files, she says:

This is Caroline. Minus the memories, but it’s her and this is exactly what Caroline would do.

In the first case, memory maketh the man (or small child). Consistency in memory is crucial for persistence. That’s not to say that all of our memories must remain intact – that would be such a high bar to meet that Heraclitus (and Pocahontas) would have been right in their insistence that we can’t step in the same river twice…

… not just because the river has changed, but because we have too. None of us would persist for very long at all.

Instead, what is commonly thought to be required is some sort of continuity. Memory is a bit like a rope: not one continuous thread, but a series of short overlapping fibres wound together. My ten-year-old self remembered the antics of five-year-old me, my fifteen-year-old self the angst of ten-year-old me, and so on. If we suddenly underwent a total memory wipe, then, according to at least some views of persistence, we’d no longer be the same person.[6]

“If you take away what they know, you take away who they are.”

In the Dollhouse case, by contrast, what matters is still psychological – Adelle doesn’t think that the blank-slate dolls are their former selves in any meaningful way, so bodily continuity isn’t enough – but something other than memory: dispositions, perhaps, or some feature of personality that guides behaviour at an instinctive level.

In consuming fiction, we seem to adapt to whatever account of persistence the text throws at us: Wolverine loses his memories but keeps his claws, astonishing muscles, and aggression; Lindsay Lohan loses her entire body in Freaky Friday, but is still easily embarrassed by her mum; Buffy remains Buffy despite coming back from the dead. Twice.

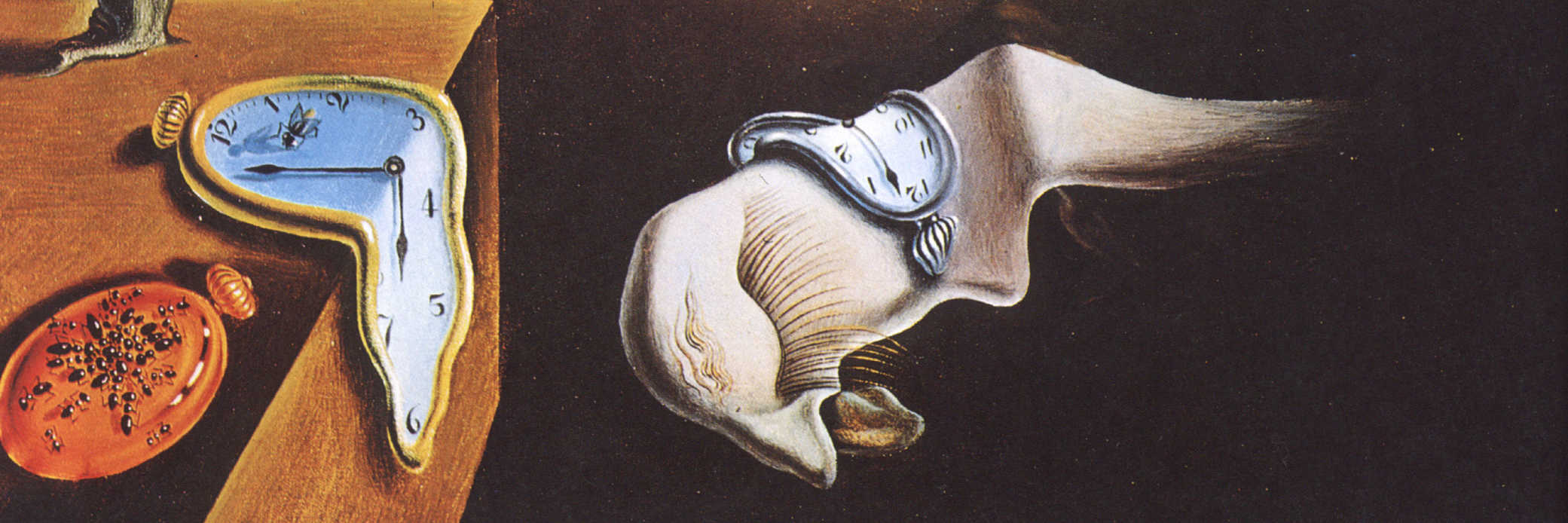

But finding the right answer to the persistence question matters, not only because it’s nice to know what sort of things make us ‘us’, but also because with new technological developments we might need to make tough decisions about what counts as surviving: if my brain is transplanted into another body, do I – the very same me – wake up in their skin? If I am vaporized in a teleporter in true ‘Beam me up, Scotty!’ fashion and then reconstructed at the other end, do I survive the trip? If time travel involves disappearing at one time and instantaneously (from the perspective of the voyager) reappearing at another, can we be sure the time traveller is the same person? A time turner is a much scarier prospect if in using it I cease to exist.

And if all of this seems far-fetched, then think about the more mundane, but hugely significant, ramifications persistence has for punishment and praise: what sense does it make to punish someone for a wrong they committed two weeks, years, or decades ago, if we can’t be sure they are the same person today? Is there any point to praising someone for the good they’ve done, or encouraging them to pursue such acts in future? We think that people do persist, at least some of the time, and perhaps that’s true... but if we’re going to be justified in attributing blame or credit, we better figure out how, and under what circumstances.

Footnotes

[1] Michael Clark, Paradoxes from A-Z, Second Edition (London: Routledge, 2007). Adapted from Hobbes, De Corpore Part 2, Chapter 11, section 7.

[2] Eric T. Olson, Personal Identity, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2016 Edition). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2016/entries/identity-personal/

[3]The Trope Namer is Kafka's 1915 Novella Metamorphosis. Spoiler: contains a beetle.

[4] Petrification is a common type of transformation where one’s survival is questioned – take the sun-drenched trolls in The Hobbit, or the victims of Medusa. A related trope occurs where characters are frozen or petrified, and then shattered.

[5] http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/QuestForIdentity

[6] Oh you’ve scrolled down to the footnote! Well done you! Let me take the opportunity to encourage you to watch the anime Ergo Proxy. It’s great, trippy, and deals with memory in interesting ways. Off you go!

References

- Clark, M. Paradoxes from A-Z, Second Edition, London: Routledge, 2007.

- Olson, E.T. Personal Identity, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2016 Edition. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2016/entries/identity-personal/

Further Reading

If you're interested in the teleportation cases or psychological continuity, see Derek Parfit's Reasons and Persons, especially Chapters 10 and 12.

Otherwise, for a comprehensive reading list, see the bibliography in Olson's Personal Identity.